How They Fell

Text by Max Pinckers

First published (Dutch version) in De Standaard, 12 July 2024

When De Standaard invited me to write about ‘the photo of my life’ I was reminded that there is no singular picture of such significance for me, but there is a photo with a telling story that captures the very moment a man passes from life into death, or of a man pretending to do so.

“Everyone is a literalist when it comes to photographs.” – Susan Sontag

In spring of 2015 I was invited by Martin Parr and Carl De Keyzer to join Magnum Photos in what would mark the beginning of a two-year experience with the agency. Having developed a distinctive and critical documentary approach, in which the exploration of the medium’s boundaries and definitions play a central role, I began researching the history of the photo agency and understood that its foundations lie in the friction between two opposing attitudes in photography; reportage, spearheaded by war photographer Robert Capa, and surrealism, with Henri Cartier-Bresson as its main driving force. This contradiction also lies at the heart of my practice as a speculative documentarian, who attempts to engage with reality and society while also including the imagination and visual poetry, and above all critically questioning oneself and the medium. When invited to write a piece about “the photo of my life” for De Standaard, it made sense to share my thoughts about a photograph that may or may not depict the exact moment of a man passing from life into death: Robert Capa’s The Falling Soldier (full title: Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936). An inquiry that led to the creation of the work Controversy (with Sam Weerdmeester) in 2017.

As a young 22-year-old covering his first conflict, Capa took or made this iconic photograph during the Spanish Civil War in 1936, and is responsible for Capa’s superstar status. It supposedly captures the very moment a soldier is shot in the head. It’s widely celebrated as one of the first photographs of war in action and became an iconic war photograph of the 20th century as a symbol of the struggle against fascism. Like many iconic photographs, The Falling Soldier was instantly controversial and debates surrounding the conditions of its making have been widely discussed ever since its creation, yet the story that accompanies it is simply too compelling not to be believed. Adding to the mystery is the fact that the original negatives are missing or lost, with only a few original vintage prints in existence.

The only record in which Capa himself talks about the making of this photograph is an interview on the NBC radio show Hi! Jinx (October 22, 1947) in which he partly refuses the usual idea of authorship when he describes how he took the photograph without looking through the viewfinder, holding the camera “far above his head” from inside the trench the moment the soldiers were mowed down by a Franco machine-gun. He sent the undeveloped film-rolls back to Paris with many others. Only when he came back from Spain three months later did he realize that he’d become a very famous photographer.

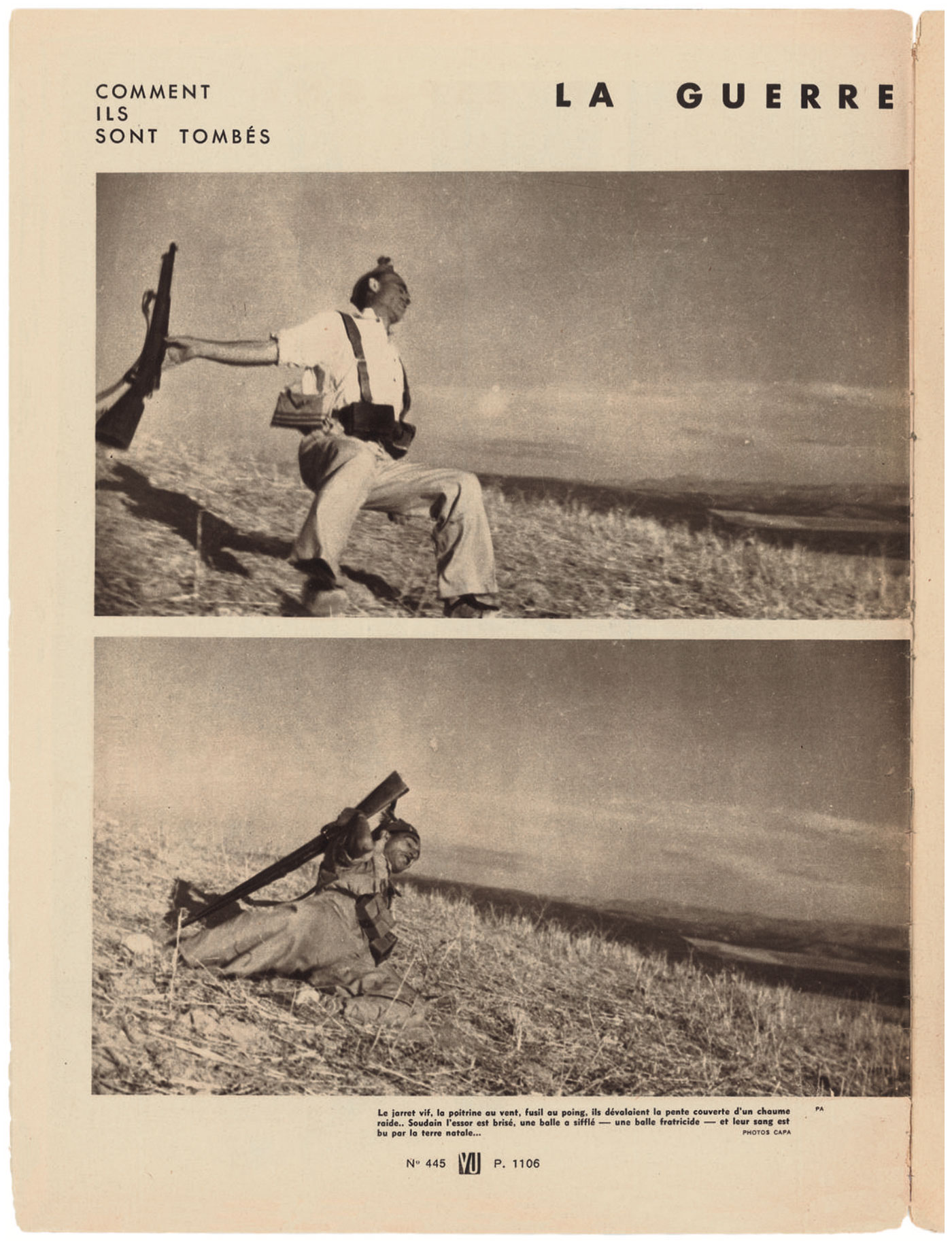

Some notes about the photograph’s publication provenance: It first appeared in the French magazine Vu in September 1936 accompanied by an image of a second falling soldier with identical framing. Both soldiers fall on exactly the same spot (revealed by the two upstanding stalks of grass in the foreground that appear intact in both photographs). Despite a soldier collapsing in one frame, there’s no dead body to be seen in the other frame. The second soldier would no longer reappear after its initial publication in Vu and was eventually forgotten in the shadow of its celebrated twin. The Falling Soldier was next published in Life in July 1937. Notably, the two photographs in Vu are in an aspect ratio of 2x3, the traditional 35mm film format, but in Life the photograph appears in a 3x4 format. Either sky was added to the image for the sake of the page layout (a common practice at the time), or the images in Vu were cropped so they could fit together on a single page. This seems somewhat trivial information, although it has caused some to speculate that if the image was not made with a 35mm camera, such as the Leica or Contax used by Capa, it may have been photographed by his companion Gerda Taro, who worked on a medium format 6x6 Old Standard Rolleiflex TLR camera. It was no secret that many pictures attributed to Capa have actually been made by Taro. Capa and Taro worked as a team, and they would frequently credit the images to Capa in order to sell more because of his celebrity and commercial success (Taro is also the one who came up with Endre Ernó Friedmann’s brand name “Robert Capa”).

The meaning of photographs is largely defined by the captions that accompany them when published in newspapers or magazines. The initial caption that accompanied the two photographs in Vu was “Comment ils sont tombés” (how they fell), which is unusual for images of such significance, and comes across as deliberately vague. It also makes me think of the playful and subversive spirit of surrealism that may have been influenced by his Magnum colleague Cartier-Bresson. When later published in Life, the caption read “Robert Capa’s camera catches a Spanish soldier the instant he is dropped by a bullet in his head in front of Cordoba.” The caption writer had apparently mistaken the soldier’s cap tassel for a shard of exploding skull. From then on, the photograph’s meaning had been set and there was no going back to the poetics of ‘how they fell’.

In 2016 I met the Spanish professor José Manuel Susperregui, who had published a paper some years earlier revealing the exact location where Capa made the famous photograph. His research was based on a series of never-before-seen photographs and how the contours of mountain ranges overlap in order to pinpoint a precise location. Susperregui was able to scientifically prove that The Falling Soldier was photographed at Cerro del Cuco near the town of Espejo, and not in Córdoba as had initially been claimed. This would place Capa 55 kilometers south of the front lines, proving it unlikely that the militiamen he was accompanying met any resistance, thus making a strong argument that the photograph was indeed staged. Historical sources and oral accounts of local inhabitants confirm that Espejo did not come under attack until 22 September, a day before the publication of the photograph in Vu and nearly three weeks after Capa and Taro left the town. Records show that Federico Borrell García, the man believed to be The Falling Soldier, did however die in battle, only probably not in front of Capa’s lens.

The landscape in the background of The Falling Soldier is blurry with little detail, making it impossible to locate through mere visual analysis. But in 2007, the “Mexican Suitcase” containing 4,500 negatives made by David “Chim” Seymour, Capa and Taro, that were considered lost since 1939, arrived by mail to the International Center of Photography (ICP). The newly discovered negatives did not contain the originals of The Falling Soldier but did reveal 40 other frames made on the same day with the same group of militiamen. In the photographs the men can be seen posing for a group photo, identifying The Falling Soldier as Borrell García by his outfit. Other photos show the men leaping over a gully and taking aim with their rifles. They are clearly not in the heat of battle, and the scenes bear all the indications of a playful game performed for the camera.

Nonetheless, Willis E. Hartshorn, the director of the ICP that holds the Robert Capa archives, has argued against the claims that the photograph is staged. He suggested that the soldier in the photograph had been killed by sniper fire while he was posing for the picture. Similarly, historian John Mraz wrote in Zone Zero that “republican militiamen were pretending to be in combat for Capa’s camera when a fascist machine gun killed this soldier just as he was posing. It is the coincidence between the fact that the photojournalist had focused on this individual at precisely the second before he was shot that makes this the most famous of war photographs.” In order to assert the photograph’s authenticity, some researchers have even performed simulations with the expertise of forensic scientists to try and prove that the soldier’s body posture and clenching hand correspond with that of a dying man.

When a selection of these newly discovered images appeared in the 2008 ICP catalog War! Robert Capa at Work, Susperregui made a connection that would allow him to discern an exact location. Three separate photographs printed on pages 59, 77, and 85 respectively, when placed alongside each other in a different order, uncovered a clear continuation in the landscape behind the action. Based on the mountain range clearly visible in the background of the sharper third photo in the sequence, Susperregui was able to triangulate the site near Espejo. He did so by sending the photo to various town councils throughout Spain. Juan Molleja Martínez, a teacher at a high school in Aguilar de la Frontera, showed the photo to his students. One of them, Antonio Aguilera, immediately recognized the landscape in Llano de Batán where he grew up. When this newly suggested region was explored, the mountain range near Espejo was eventually identified as the one seen in Capa’s photographs.

Capa had experience in orchestrating reenactments. One year after The Falling Soldier, he became involved in staging large-scale reenactments of republican attacks on fascist positions in Spain for the monthly newsreel The March of Time, led by American magazine magnate and founder of Life Henry Luce. In documentary films with a propagandist undertone, staging was encouraged and eagerly anticipated by the public of the time. Luce defined it as “fakery in allegiance to the truth.” In his book The Documentary Impulse (2016), Magnum photographer Stuart Franklin writes that “no one batted an eyelid on 24 June 1937, when Capa staged an entire attack scene in Peñarroya, northwest of Córdoba, where according to diaries written by the general in charge of the garrison ‘an imaginary fascist position was stormed as men, with terrifying roars and passionate battle-lust, leaped and bounded double-time into victory’.” According to the same diary, Capa was pleased with the staged attack and wrote that “an actual attack wouldn’t look as real as this.” Not long after, Capa would preach the famous lines “No tricks are necessary to take pictures in Spain. You don’t have to pose your camera. The pictures are there, and you just take them. The truth is the best picture, the best propaganda.”

We think that photographs, especially in photojournalism, must maintain some kind of integrity toward their authenticity, but the history of iconic photographs proves quite the opposite. Most iconic pictures are shrouded in controversy that alludes to their mythical powers. That they are often known to be staged, manipulated, or mistook in some way (be it reenacted, performed, retouched,...) means that the public is generally not concerned with placing the authenticity of an image above the emotional and societal meaning it has attained. Most iconic photographs stand in for an event that they do not literally represent. They take on an emblematic function, like monuments, in which they often symbolically stand for something rather than the actual situation they depict. They are experienced collectively and cannot claim a singular truth. In the case of The Falling Soldier, we simply choose to believe the better story; that this is shot in the very split second that a man leaves his body.

Allow me to speculate about another story. Did Capa pre-enact the death of loyalist militiaman Federico Borrell García? Were Capa and the group of militiamen, maybe, just fooling around out of the boredom behind the front lines, and decided to enjoy themselves in making spectacular photographs of a simulated battle situation, just like they knew from the newsreels? I like to believe that Capa was confronted with the self-fulfilling prophecy and power of his own photographs when he created an image that foretold the death of the soldier he had playfully collaborated with. Torn between the weight of Borrell García’s death and maintaining the mythical status of this image along with the fame it brought him, he felt a deep sense of guilt and responsibility for the soldier’s death. Before he had a chance to admit that the photograph was staged, it was already too late, and it would have cost him his career as a photojournalist. Despite his good intentions, the secret burdened him throughout life. Hence, his reticence to discuss the photo, as well as a certain confusion in recounting the circumstances surrounding the photograph’s making, and perhaps his subsequent attraction to reenactments.

The two photographs as they first appeared in Vu, September 23, 1936. © Vu/courtesy collection Michel Lefebvre